STEVEN M. COZART

2023 Brightwork Fellow

ARTIST STATEMENT

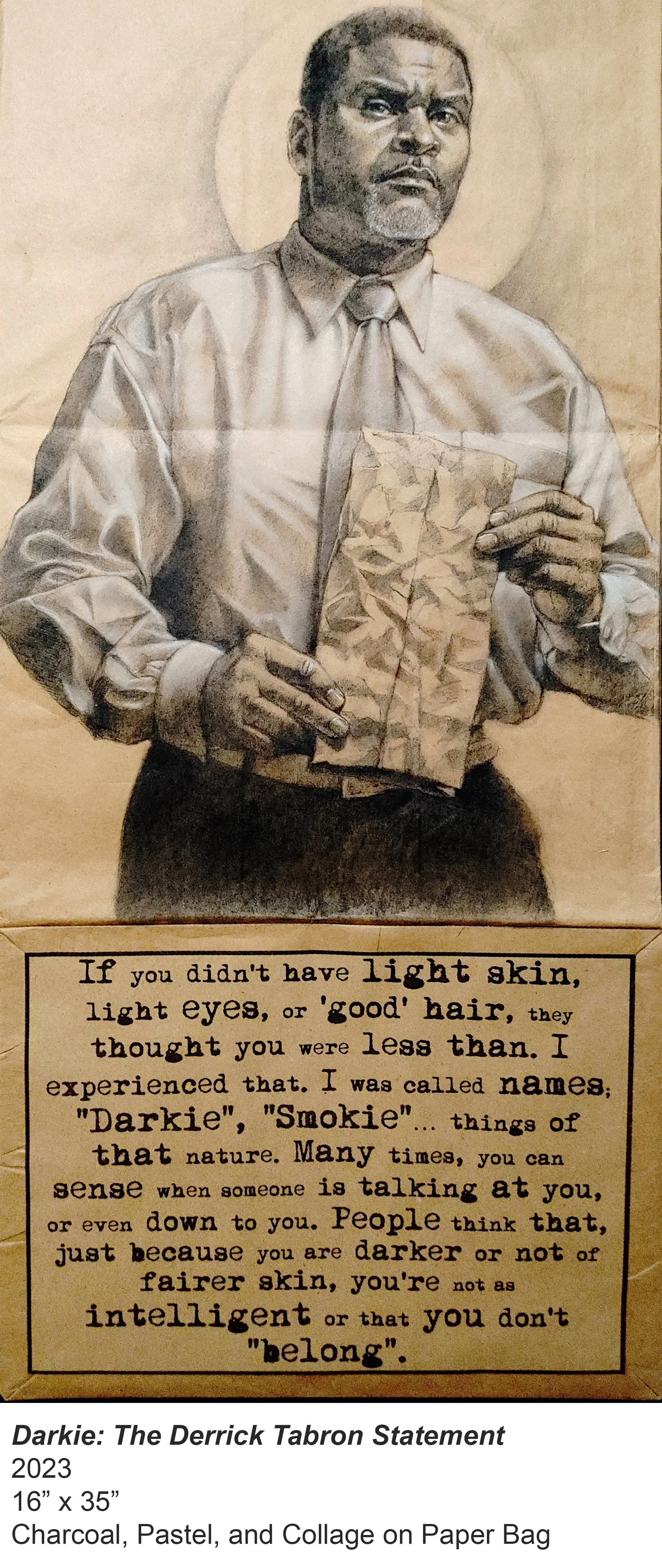

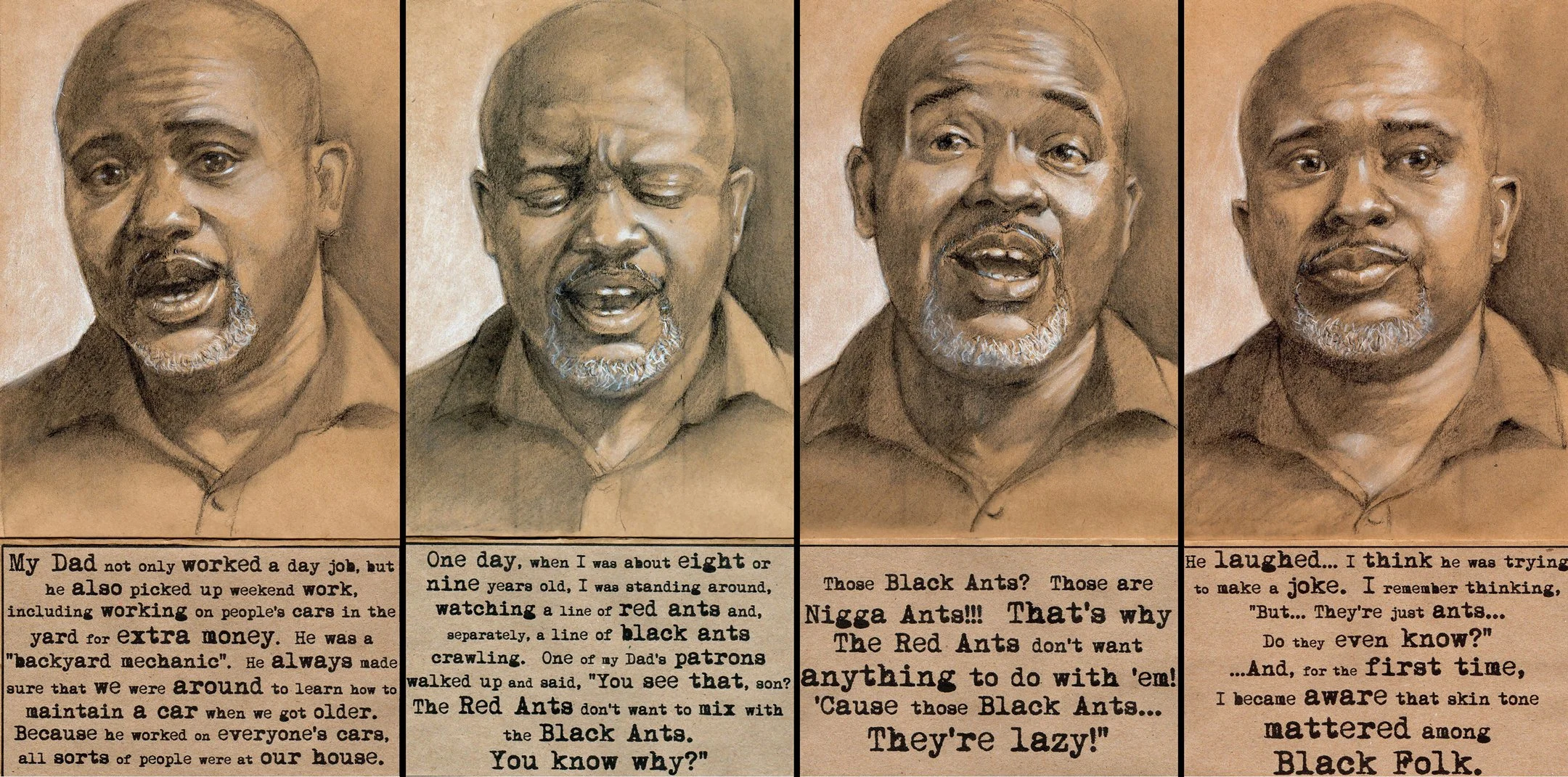

My work as of late is reflective of my thoughts and feelings about race and identity in America, focusing on stereotypes of the Black Male and Female within the paradigm of the Black Community. Specifically, I have noted the use of codecs (devices that compress and decompress data to enable faster transmission of that data) within the community to quickly pack and unpack information about Black men and women amongst themselves. These codecs have taken and may take many forms, such as a brown paper bag (as related to skin tone), or a pencil (as related to hair texture), to name a few. The tones, hair textures, and even features of the individuals also serve as codecs.

My ongoing body of works (drawings, paintings, and mixed media assemblages) refer to such things as the historical practice, in Black communities, of colorism (prejudice or discrimination against individuals regarding their skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial group), texturism (the idea that certain types of natural hair patterns are more desirable or beautiful than others, especially if they mimic European hair), and featurism (the social acceptance and/or preference of European facial features over African facial features). In fact, these comparisons are based upon several superficial traits, myths, and fallacies prevalent in the community.

Acts of colorism would include, for example, comparing a brown paper bag to skin tone in determining manhood, beauty, and admission or exclusion in social circles. In fact, there are some that are of the opinion that virility and masculinity for Black Males has a direct correlation to skin tone, while beauty or desirability of the Black Woman has a direct correlation to skin tone.

Acts of texturism would include using a pencil to make a judgement on the grade of an African American woman’s hair, thereby deeming it as “good” or “bad.” There is even historic documentation of using the Pencil Test to deny access to establishments and social group or gatherings.

Acts of featurism would include choosing or making judgements of individuals based on facial traits (nose, lips, eye color) that are closer to European beauty standards in America.

Using these concepts as a point of departure, a variety of images are generated.

These notions are problematic, as they set up division within the Black Community. This can even become as complicated as encouraging acts of misogyny, misandry, bullying, and “light skinned privilege’, just to name a few of the unfortunate circumstances that the very members of the community exercise towards each other.

This is of interest to me because of the irony of the situation. The history of the Black American in this country is a dark, inhumane one that has its roots within the same type of ignorance. Why, then, would it be repeated within the same community that suffered it? Is this the oldest example of the Stockholm Syndrome, or the embodiment of the term ‘slavery hangover’? Up to this point, I have found and interesting paradigm: while it is obvious that some within the Black community pass judgment on others within the community based upon perceived notions about physical appearance, there is no clear answer, no right or wrong in this regard. Some are made to feel less than because they have a dark complexion or choose to wear their hair in a natural state, while others, such as my mother, have their very identity and loyalties questioned because they are considered “too light”.

As revealed in interviews with my subjects, the use of codes and ideals of colorism, texturism, light skinned privilege, and bullying are still prevalent in the community today. Using a variety of these codecs (brown paper bags, Snellen eye charts, scissors, value scales, etc.,) I record these accounts of skin tone, hair texture, manhood, womanhood, etc. as a complicated issue and experience: different for each African American.

The goal of the work is to begin a conversation within public spaces about why these ideals are so prevalent within the Black Community, given the community’s history in the United States. The hope is that the conversations lead to a transcendence of these systems among the Black Community at large.

BIO

Steven M. Cozart was born and raised in Durham, North Carolina, and now lives and teaches in Greensboro, NC.

Cozart is an artist, educator, and documentarian that loves to draw and, despite being colorblind, enjoys painting. His body of work is figurative and reflects thoughts and musings regarding his own life, circumstances, and interactions that he experienced. As of late, his work has begun to reflect his thoughts and feelings about race and identity in America, focusing on stereotypes of the African American Male and Female within the paradigm of the African American Community, imploring the symbolic meanings of objects within the imagery.

Cozart’s works and imagery on Colorism, Texturism, and the perception of the Black Male in America have been exhibited at multiple museums and galleries along the East Coast and South, including the Sigal Museum, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art, the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, Weatherspoon Art Museum, The Nasher Museum, Green Hill Center for North Carolina Art, and the Brooklyn Collective.

Cozart’s work is also part of several notable collections, including the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, Weatherspoon Art Museum, La Salle University Art Museum, the Ackland Art Museum, and the Reubenstein Library at Duke University.

In 2016, Cozart was awarded the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

In 2022, Cozart was featured in several publications, including “Art of The State: Celebrating the Visual Art of North Carolina”, a book by Liza Roberts, documenting the vast array of artists and works in the state of North Carolina. Cozart was also included in “Shifting Time: African American Artists 2020 – 2021”. Co-edited by Klare Scarborough and Berrisford Boothe, this book offers a glimpse into the lives of over 70 selected African American artists during the early years of the pandemic.

In addition to being a practicing artist, Cozart also has been a visiting lecturer for Syracuse University, the Weatherspoon Art Museum, Duke University, East Carolina University, North Carolina A&T State University, and the Harvey B. Gantt Center for Arts and Culture.